LIKENESS

& LITHOPHANE

The term ‘likeness’ in popular usage is almost exclusively associated with portrait photography and portrait painting. So powerful is this association that to ask the question “is it a good likeness?” is to immediately evoke portraiture. This wasn’t always so. In Likeness and Presence, the German art historian Hans Belting demonstrated that from late Antiquity and well into the Middle Ages in Europe, and presumably coevally in ancient cultures that used sacral images such as the Australian Aboriginal Nations, the material image was a tangible presence, not a likeness or resemblance.[1]

During the twentieth century, many artists eschewed photographic likeness in their prints, seeking instead to use the character of the medium to capture the character of their subjects, who might be family members, as the examples by John Brack and Otto Dix in this exhibition demonstrate.

[the works by John Brack in the exhibition are: John Brack Third Daughter 1954, etching, 17.3 x 12.2cm. Newcastle Art Gallery. and Fourth Daughter 1954, etching, 17.3 x 12.4cm. Newcastle Art Gallery.]

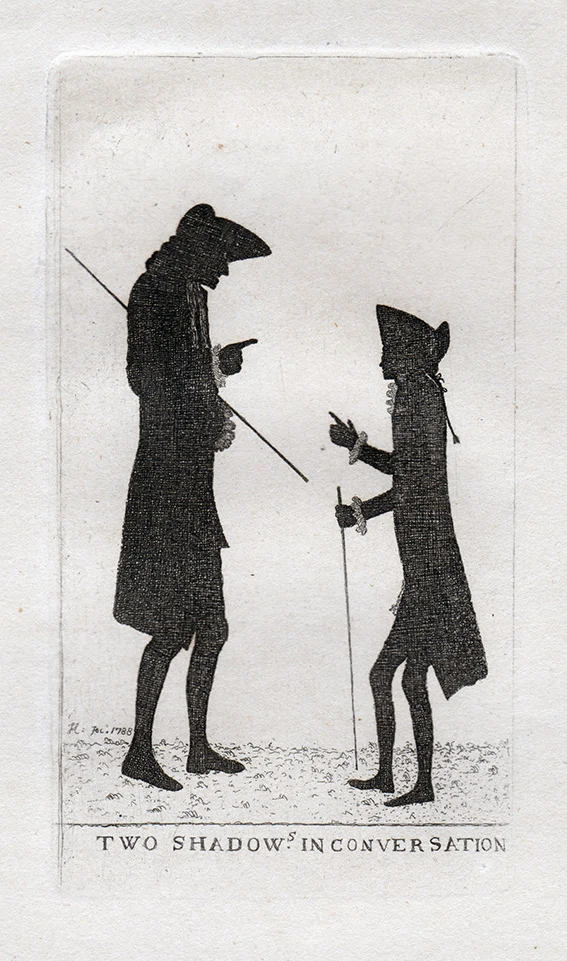

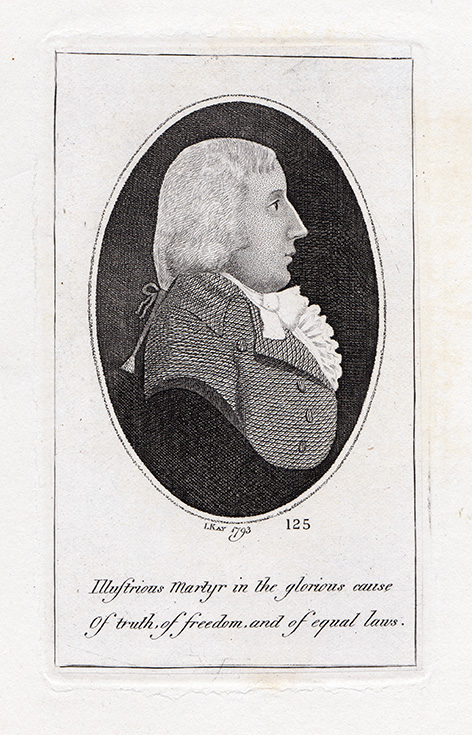

In the early industrialised world, variations of the shade or silhouette were the dominant form of portraiture for half a century, presenting a representation limited to a single profile contour (see “Silhouettes”). Nevertheless, the shade was considered to have substantial evocative power; for instance, Goethe fell in love with the woman he hoped would be his future wife from a single viewing of her silhouette. By 1800, artists had available to them engraving techniques on copper and wood to produce the most refined realistic likeness but such was the urge to find a classicised regressive or refined focus on outline that, as with the silhouettists, portrait engravers favoured the profile portrait. An example is Scottish artist John Kay’s engraved portrait of Australia’s first political prisoner, the revolutionary Thomas Muir, who was sentenced in Scotland for sedition in 1794 and transported to Sydney in 1795. Kay also produced the etched silhouette portraits of Lord Kames and Hugo Arnot (1788), which he titled Two Shadows in Conversation.

[1] Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1994).

Otto Dix Nelly with the Lace Collar 1924, lithograph, approx.. 28 x 20cm. © Private collection.

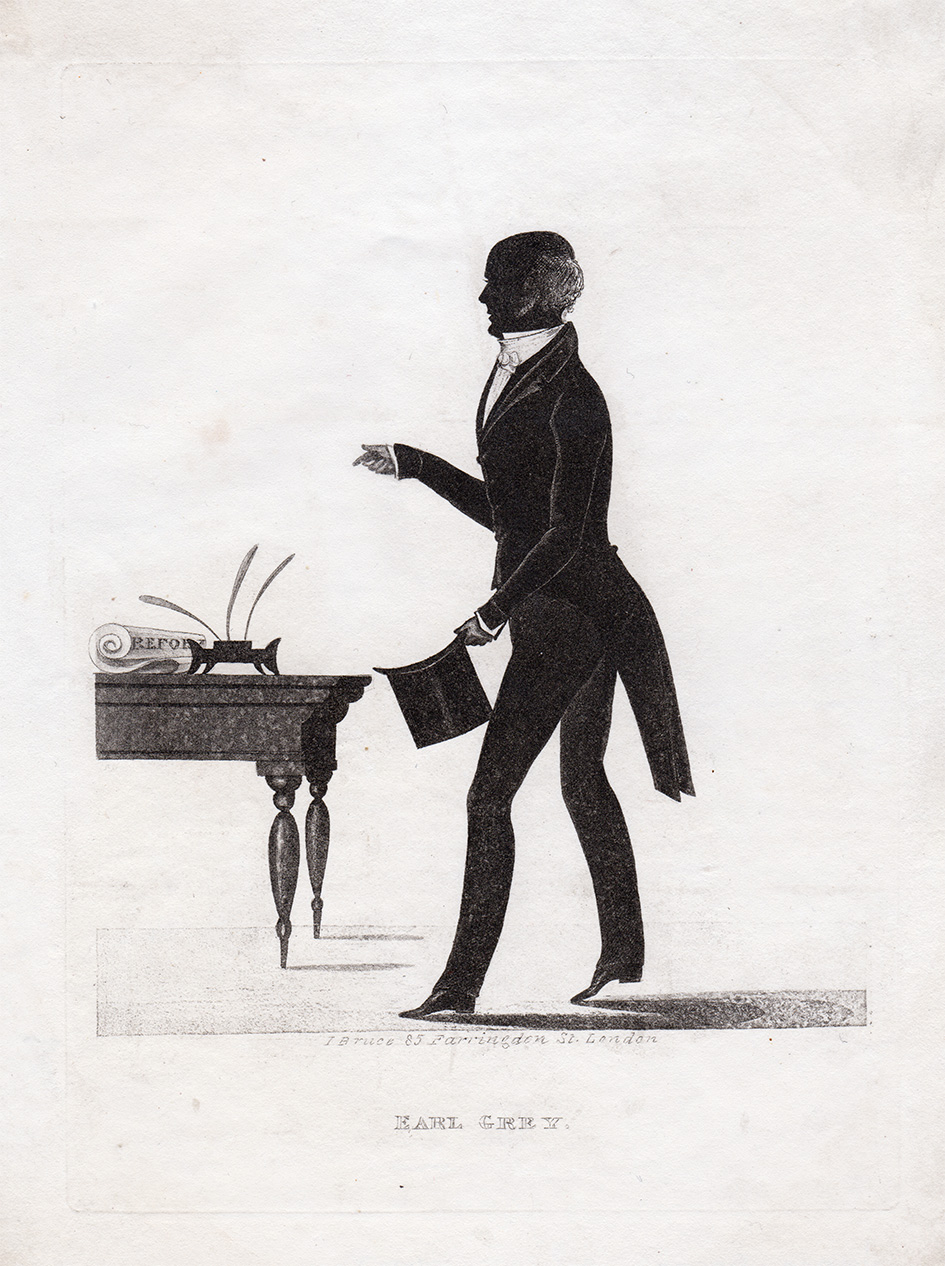

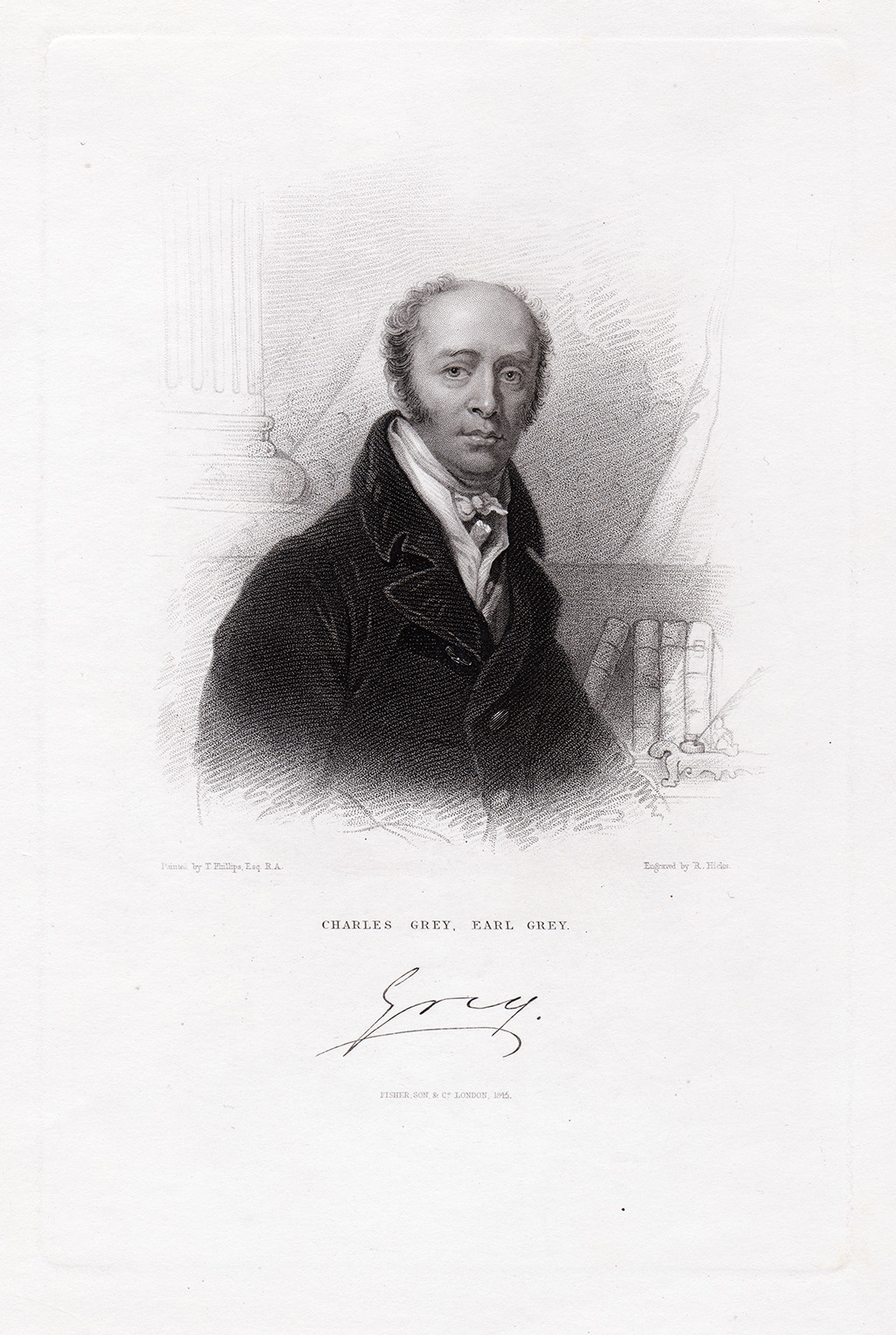

In 1831, the British Prime Minister Earl Grey (yes, the tea carries his name) reviewed the land grants system in the Australian colonies, which resulted in land regulation reforms, bringing an end to free grants and providing for sales by auction at a minimum price. John Bruce’s silhouette portrait of Earl Grey from 1831, with the ‘report’ on the table, presumably records Grey’s ‘service’ to Australia. He is sometimes presented as a friend of the colonies, although the record of his speeches in the British Parliament contradict that view. In 1850, he did raise the idea with Governor Fitzroy of establishing a government-sponsored, interracial system of children’s boarding schools that would force the assimilation between settlers and Aborigines of New South Wales. That strategic use of children to advance government policy involved stealing the children of both colonist and Aboriginal families alike. The later portrait of him by Phillips (1845) makes a good contrast with the silhouette, since it is engraved in the crayon manner as a conventional likeness

Although interest in the silhouette form was reactivated two decades ago by the contemporary artist Kara Walker, it was relegated to a fair-ground novelty as a portrait mode with the arrival of the daguerreotype, ambrotype, and, above all, the albumen-printed carte-de-visite form. Nevertheless, the profile likeness continued as the favoured choice on coins and medals until well into the twentieth century. A likeness on coins was usually reserved for a monarch or deity (one and the same, quite often) but commemorative medals often celebrate individuals. An early example of such a medal issued in New South Wales depicts Aboriginal warrior Warrah Warrah (1794–1863), whose name became William Warrell or Billy Warrell. In the latter years of his life, when crippled by paralysis in the knees, he became known by the affectionately dismissive name of ‘Ricketty Dick’. This large medal (4.7cm diam.) was made by Julius Hogarth in 1873 for the NSW Intercolonial Exhibition Hogarth must have met Warrah Warrah—who had a permanent camp set up at Rose Bay on the South Head Road, Sydney—soon after his arrival from Denmark in 1851. This is evident, as Hogarth used him as a model for a silver statue of an Aboriginal warrior exhibited in the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1855.

Installation view Newcastle Art Gallery. (photo: Tobias Spitzer) This display features the contemporary use of the silhouette by Pamela See . The images and objects in the display case and on the wall above highlight the dominance of the silhouette at the beginning of the nineteenth century and the photographic portrait at the end. More importantly, the dates of the various images reveal the coexistence of older forms such as copper and wood-engraving along with new photographic processes.

Julius Hogarth New South Wales Intercolonial Exhibition c. 1870, white metal, 4.7cm diam. Private collection.

Installation view Newcastle Art Gallery (photo: Tobias Spitzer) Collection of coins and Medals including the three versions of Warrah Warrah and right: Ryan PRESLEY 1987- Blood Money 2018 Obverse and reverse of a series of ink-jet printed nanofilm notes Private collection; Ryan PRESLEY 1987- The Good Shepherd poplar woodblock and gold leaf Artist collection

The commemorative medal shows a younger version of Warrah Warrah to represent a generic Aborigine. Only on this medal was his likeness unnamed, however. The Melbourne firm of Stokes and Martin, which made the large and expensive medal, set up a demonstration foundry at the exhibition to strike smaller (2.2cm diam.) medals in bronze, using this portrait die, encircled with the inscription “Ricketty Dick”. Stokes and Martin used the same strategy to advertise their medal and token-making prowess at the Victorian Exhibition in Melbourne (1872–1873), except it replaced “Ricketty Dick” with “Billy ex Rex Vict” [King Billy Victoria]. In the same foundry scenario at the Brisbane Colonial Exhibition in 1876, the same die was used but the caption simply read “Sandy ex Rex” [King Sandy]. The image was also used on medals minted in 1872 as Christmas gifts. This die-struck image continued to circulate until the end of the nineteenth century, appearing on a medal for the Albury Industrial Exhibition of 1896 and on obverse of “The Pioneer“ medal, Melbourne in 1899. It is difficult to imagine an Anglo-Australian likeness becoming an interchangeable or generic likeness for the abstraction of a colonial state or nation as has happened here. Whatever agency this image promoted for its subject, beyond aesthetics, can be guessed by the fact that many of the surviving medals, in bronze and silver, are like the three shown here—holed—so that they could be worn by their colonial owner. However, such is the anachronic power of the material image: when a transaction occurs in the alignment of these medals in the exhibition with Ryan Presley’s Blood Money (2018) series of ink-jet printed nanofilm notes, Warrah Warrah is reanimated as the powerful young warrior he once was.

(Ross Woodrow Aug 2019)

James Neagle (1760-1782) Ben-nil-long. c. 1798, 1O x 13.5cm. copper engraving. Private collection

Woollarawarre Bennelong (c.1764?) was a senior man of the Eora people of the Port Jackson area and belonged to the Wangal clan of the south side of Parramatta River.

Bennelong was brought to the settlement at Sydney Cove in November 1789 by order of Governor Phillip. He escaped after three months but later returned, keeping in contact with Phillip. In 1790, Bennelong asked Phillip to build him a hut on what became known as Bennelong Point, now the site of the Sydney Opera House.

LITHOPHANE

Installation view of lithophanes, Newcastle Art Gallery (photo: Tobias Spitzer)

Another compelling proto-photographic material image in the nineteenth century has been completely ignored by all the print and photographic theorists, with the possible exception of Barbara Stafford.[i] This was the lithophane which was a popular reproductive form created by pressing or mounding a concave design into a thin sheet of porcelain. When the porcelain tile was backlit with candle or window light the different densities of porcelain created a grey and white ‘photographic’ effect. Developed in England and Germany in the 1820s, lithophanes remained popular throughout Europe and the United States long after photography was widely practiced as examples from 1860 and 1890 made in the Royal Porcelain Factory in Berlin demonstrate. These quality examples illustrate the ability of the form to reproduce tonal nuance and detail of contour. They are fragile objects, given that the porcelain must be relatively fine to keep the highlights as wafer-thin as possible, but this does not explain their total neglect; especially considering they represent a closer kinship to the radiant image on a digital tablet than any other in the nineteenth century.[ii] Their difference from the digital tablet makes them particularly important in the context of this exhibition in that they are most emphatically material. The lithophane’s transfer from a concave, almost indecipherable form, to a fully realised convex impression establishes its direct descendance from the cylinder and related seals from the Ancient Near East, and the seals and signet rings of Classical and Medieval Europe, but the magic of the transformation is achieved with light, not by a physical impression.

[i] Two lithophanes were included in Barbara stafford’s exhibition Devices of Wonder 2001 at the Getty in the section “Light and Virtual Substance” catalogue numbers 342 and 343, (p.390 in catalogue) although these were not discussed in the catalogue.

[ii] I’m not forgetting the magic lantern slide which required the lens equipped lantern apparatus for the slides projection. I’m also cognisant of the aversion art historians have to popular images that were the majority of subjects for the lithophane; pretty couples, dogs and cute children. When it comes to children, “serious” art favours the more regressive representation such as those by John Brack and Otto Dix shown in the exhibition.

R. Woodrow

Couple and dog, Porcelain lithopane, c. 1890 (K.P. M) Royal Porcelain Factory, Berlin (no 392 “G”). 18.4 x 15.24 cm

Copyright © All rights reserved

![Julius Hogarth Brisbane Exhibition Mint "Sandy ex Rex" [King Sandy] 1876, bronze medallion, 2.3cm diam.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d0a492836336000012bc86d/1567710787540-3DXUGD5M1AIXYZT6ZS5U/medal-sandy.jpg)

![Julius Hogarth Melbourne Victorian Exhibition Commemorative "Billi ex Rex" [King Billi] 1872, silver medallion, 2.2cm diam.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d0a492836336000012bc86d/1567710777565-EAAEZSA8HCNYACJP57WI/KingBILLI.jpg)